Artspeak

Cathy Busby

Cathy Busby is an artist based in Halifax and Vancouver. She has a PhD in Communication (Concordia University, Montreal, 1999) and was a Fulbright Scholar at New York University (1995-96). She has an MA in Media Studies (Concordia University, 1992) and a BFA (1984) from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. She has been exhibiting her work internationally over the past 20 years.

Exhibitions

-

CATHY BUSBY, DAVID MACWILLIAM, RACHELLE SAWATSKY, KRISTA BELLE STEWART

June 7–July 26, 2014Not long ago, Boris Groys claimed that artworks are inherently sick and require a curator to heal them by including them in an exhibition.[1] While this was meant as more of a rhetorical flourish than a programmatic statement, it nevertheless highlights the power imbalances that permeate both art and therapy as ideas and practices. The works in this exhibition reconsider some of the many historical and contemporary intersections of art and therapy, seeking, in the process, to question those very power imbalances. Contrary to at least one recent take on this theme, each of the works in this exhibition demonstrate that not all art is therapeutic, nor that its aim should be to make everyone happy.[2] Where Does it Hurt? brings together four artists whose work thematizes therapy, or the idea of the therapeutic understood broadly as a treatment meant to relieve or heal. These works rethink the relationship between art and therapy, looking askance at received therapeutic methodologies, and, especially, established analogies between therapy and the way we encounter and interpret works of art. The formal differences between these works are matched by a corresponding range of scales upon which they imagine the therapeutic encounter: from the epistemological to the individual to the social and political. My hope is that the implicit ellipses between these works will allude to the wide range of approaches artists are taking towards this theme but that necessity prevents including here.[3]

While Groys’ statement points to the long and often problematic relationship between therapy and the interpretation and distribution of artworks, not all of the connections between these two fields are metaphorical. Carlo Ginzburg, for example, details the influence of connoisseurial art history upon Freud’s psychoanalytic method in its focus on marginal details.[4] As Ginzburg points out, Freud himself acknowledged his debt to Giovanni Morelli, who held that brushstrokes contained an essential trace of the artist’s hand; a belief that presaged Freud’s own claims about the significance of previously overlooked psychological symptoms.

It is to this shared history that David MacWilliam’s large-scale weaving, Inkblot 031 (2013), calls attention. Using the same method that Herman Rorschach drew upon to create his famous Psychodiagnostik tests in the 1920s, MacWilliam has gone a step further by enlarging his inkblots and translating them into vividly coloured tapestries. The back of the tapestry, which is exposed in its current hanging, is not the exact inverse of the blot on the front, but is rather a colourful melange of excluded threads that is tempting to think of as a manifestation of the work’s own unconscious. The jacquard looms upon which this work was made are themselves significant for being among the first forms of automated weaving. Through these layers of mediation, MacWilliam points to the assumption held by early twentieth-century psychologists, and their surrealist contemporaries alike, that automatism could offer a transparent insight into the unconscious. In doing so, this work underlines how the accidental mark, and other traces of automatism, became a privileged stylistic effect that even now is strongly associated with the perceived realism or objectivity of a representation.

Rachelle Sawatsky’s paintings also work in and around received analogies between pictorial and psychological depth. In particular, her series The Apple and The Doctor (2012) invites observers to read psychological meaning into egg tempera doodles on found stationery from a psychotherapist’s office. Such readings are easier when the figures and objects are more clearly delineated, but many of the paintings also resolutely evade interpretation. At the same time, those that do depict rarely slide into familiar diagnostic narratives. One begins to question the scenario these works implicitly stage. Are they the product of an imagined analysand’s earnest attempts to express her inner desires and motivations, or a strategic defacement? The abstract, hazy colours of Sawatsky’s large stretched canvases—both untitled (2014)—also resist narrativization, exploring instead the affective capacities of colour, shape and scale. Sawatsky describes some of her paintings in this style as “relaxing,” questioning, in the process, models of therapy that privilege the search for hidden meanings over affective responses.

Whereas the preceding works think of therapy on an individual level, or in terms of a two-person relationship—the patient and the doctor—the following projects approach therapy on a broader scale. Krista Belle Stewart’s two-part video installation embodies and reflects upon another potentially therapeutic encounter that is both intensely personal and political. It tells two parallel stories about the life of the artist’s mother, Seraphine Stewart—the first Aboriginal public health nurse in British Columbia—with a focus on the elder Stewart’s experience as a former student at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. The installation at Artspeak is one of three works by Stewart drawing upon the same source material that are currently on display in Vancouver. The other two are public installations at the City Centre Canada Line station and on dual video screens above Robson and Granville streets, both of which were commissioned by the City of Vancouver Public Art Program as part of Vancouver’s official Year of Reconciliation, which coincided with the National Event of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada held here in September 2013. At Artspeak, one wall features an unaltered projection of the CBC docu-drama, Seraphine: Her Own Story (1967), which portrays the life of the elder Stewart leading up to and shortly after her nursing studies. In this video, the artist’s mother plays her younger self in a series of scripted scenes that are shot in grainy black and white and impressionistically montaged over a jazz soundtrack. Projected on the opposite wall are a series of video excerpts from the elder Stewart’s personal testimony for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.[5] The dissonance between these two videos—one in which Stewart’s mother tells her own story and another where she reenacts a version of her life according to someone else’s script—is emphasized by the way they confront one another across the screening room. It is significant that Stewart refuses to reconcile or apply new narratives onto her source material. Reckoning with the effectiveness of the TRC itself as an instrument for personal catharsis, political therapy and future societal change will require many years and much debate. In the meantime, Stewart’s work highlights the potential power of simply revealing the personal accounts of former residential school students.

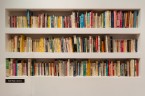

The curators of The Talking Cure—a recent group exhibition at Oakville Galleries that featured works from Andrea Fraser and Melanie Gilligan, among others—describe a kind of political therapy wherein artists appropriate palliative methodologies from psychoanalysis or hypnotherapy to externalize structural societal ills.[6] Cathy Busby’s Self-Help Library (1994) takes a slightly different approach, focusing instead on gathering material evidence of those same societal ills. The library itself consists of an archive of close to 300 self-help books, ranging from pulpy bestsellers—aimed at correcting “inefficient behaviours” and the like—to empowering feminist manuals for adult survivors of child abuse. Self-Help Library embodies a socio-historical record of (purported) therapeutic cures, and, by extension, also of the tremendous constellation of anxieties and ailments that afflicted the largely English-speaking North American society within which these books originally circulated. In spite of not having incorporated new titles since its last iteration in the 1990s, Self-Help Library is now once again an active therapeutic resource for those who page through its volumes seeking a do-it-yourself means to healing.

Busby’s work was originally assembled for an exhibition at the New Museum in New York in 1994, only to be remounted two years later at the Banff Centre’s satellite gallery in Calgary. There, it was shown along with several related works, including a version of the poster, This Book Can Change Your Life, currently on display in the front window of Artspeak. The present exhibition takes its name from the latter exhibit in Calgary, which was also called Where Does it Hurt? This gesture underlines the structures of repetition that the works in this show use to think through art and therapy: from the front and back of the tapestry, to the play between flatness and depth in the paintings, to the juxtaposed video projections, and, finally, the library’s archive of ailments and cures. I hope the choice of title will be understood both as a tribute to Busby’s long-term engagement with art and therapy as well as a way to acknowledge the historical precedents of the current renewed interest in this topic.

NOTES

1 Boris Groys, Art Power (Cambridge, Mass.; London: The MIT Press, 2013) 46.

2 I am referring to Art as Therapy, a blockbuster exhibition curated by Alain de Botton and John Armstrong currently on display at The Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), The Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam) and National Gallery of Victoria (Melbourne). An excellent critique of this show is available here.

3 Where Does it Hurt? will also not touch upon art therapy, an entire discipline and field of discourse quite apart from the histories of art with which the works in this exhibition engage.

4 Carlo Ginzburg, “Clues: Roots of an Evidentiary Paradigm,” History Workshop 9 (Spring 1980): 5–36.

5 The TRC was established as part of the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement in 1998 and builds on the model set by a similar commission in South Africa that arose from the aftermath of Apartheid. The TRC has a mandate to find out the truth about what happened at the government-funded, church-run schools, to inform all Canadians about its findings and to initiate a process of healing and reconciliation. Over more than 100 years, more than 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children were brought to these schools in an effort to systematically “kill the indian in the child” by eliminating parental involvement in virtually all aspects of the childrens’ upbringing.

6 Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh’s catalogue essay for The Talking Cure is available here.