All quotes are from interview transcripts included in Talk: a postscript to some recorded conversations about art and text, in and around Vancouver1 unless otherwise noted.

Picture the bar at Vancouver’s Cecil Hotel, not as the strip bar it was until it was torn down in 2010 to make way for a 23-story residential development, but as it had been back in 1970 when it was the kind of gritty bar that attracted journalists, university students, poets and artists among other regulars.2 Now imagine artist/poet Roy Kiyooka, hair growing long, fiddling with a new device to record the conversation. About these recordings, he had said, “At the Cecil …the nature of what occurs as conversation is that thing: it is not discriminatory, it never stops, and it is totally impartial as to what is uttered or said.”3 Roy Kiyooka’s fascination with recorded conversation evokes a set of coinciding and growing artists’ interests in mechanical recording, communications and sociality —— interests that were apparently particularly strong in Vancouver.4 Such recordings also indicate an interest in the point where the improvisational meets the indexical, along with the desire and the curiosity to explore new media. Perhaps for some the indexical "snapshot-of-life" quality provided by such recordings was seen as a way to “get real.” For the painter-poet it had to do with curiosity about language; it was about poetics and expression over straight documentation, and about the potential of language as an alternative medium to paint. It is well known that by 1970 Roy Kiyooka had turned away from his work as a painter to explore text, photography, music and performance in what became an expansive intermedial practice; as Scott Watson had said, “He was admired by many in the Vancouver scene because his practice was so hybrid.” Kiyooka’s turn away from painting and medium-focused modernist abstraction was in accordance with the times and in line with multimedia artistic tendencies taken up as alternatives to a narrow Greenbergian Modernism that by the end of the 1960s represented the fully institutionalized art of the establishment.5

Swept up in desires to reform society and energized with an optimism, curiosity and excitement about new technologies, art was also becoming more textual from the late ‘60s into the ‘70s, most obviously in Conceptual art, but also in Minimalism and Pop, along with interdisciplinary work and performance practices that could be scored or scripted. At the same time Canadian arts funding encouraged experimentation with new media, most notably with a large Canada Council grant for Intermedia in 1967.6 A decade later, building on the activities of the new artist-run centres and increased artist access to video and photographic equipment, some Vancouver artists would take note of the influential Pictures exhibition that took place in New York in 1977. While the show was called “Pictures”, text was key. The exhibition was anchored by the now-famous “Pictures” essay by Douglas Crimp and featured work that referenced mass media images, mostly taking form as photographs and video —— these images were theorized as textual in that they could be understood and analyzed in ways connected to language. Crimp ascribed a certain aim to them, “To understand the picture itself, not in order to uncover a lost reality, but to determine how a picture becomes a signifying structure of its own accord.”7

Approaches that brought aspects of linguistic theory to bear on visual art were heavily influenced by Roland Barthes’ texts on signification, photography and the “death of the author.”8 In the ‘70s and ‘80s, curators, art critics and artists were searching for alternate foundations, working on theoretical positions against Greenberg’s theory of modern art and opposing themselves to any traces of romantic transcendentalism. Poststructuralist and psychoanalytic theories were championed by influential art critics, curators and art historians; by the ‘80s, textuality along with a return to representation and mechanically-made images had become unspoken requirements for many artists. As suggested by William Wood:

A dominant idea circulating in the ‘80s is that photographic, cinematic and televisual images do not come without text of some sort attached. This idea was attached particularly to mechanically-made images. That’s why painting was abjured. It may have had a very strong textual support, but painting itself is not considered linguistically-based, whether that’s true or not. You can’t linguicize painting the way you can photography, by relating it to those textual supports that exist within media culture.In the ‘80s, textual analysis, deconstructionist methods and semiotic studies flowed into practices taken up by many artists who aligned themselves with a leftist critique of culture, one predominantly associated with photography as art. Paradoxically, text and language evade our analytical grasp at some point, a condition we experience even more so today as a general condition of textuality has enabled a fluidity and volume of both searchable and hidden text and images —— as algorithms, data and complex code structuring the flow of data —— beyond any imagined expectations back in 1970 when artists associated with groups such as Intermedia had absorbed McLuhanesque ideas with enthusiasm.9 Kiyooka’s objectification of conversation as “that thing” that is “not discriminatory” and “never stops” feels peculiarly prescient when considered in hindsight from a 2015 perspective with non-stop Twitter feeds and a general raising up of “conversation” in status in the art world to the point where it “never stops” leaving little time for reflection on what’s been said.10 Talk: a postscript to some conversations about art and text invites a reflection on not only what’s been said, but on how and why, and within and around what vectors and thresholds of visibility, value and meaning making.

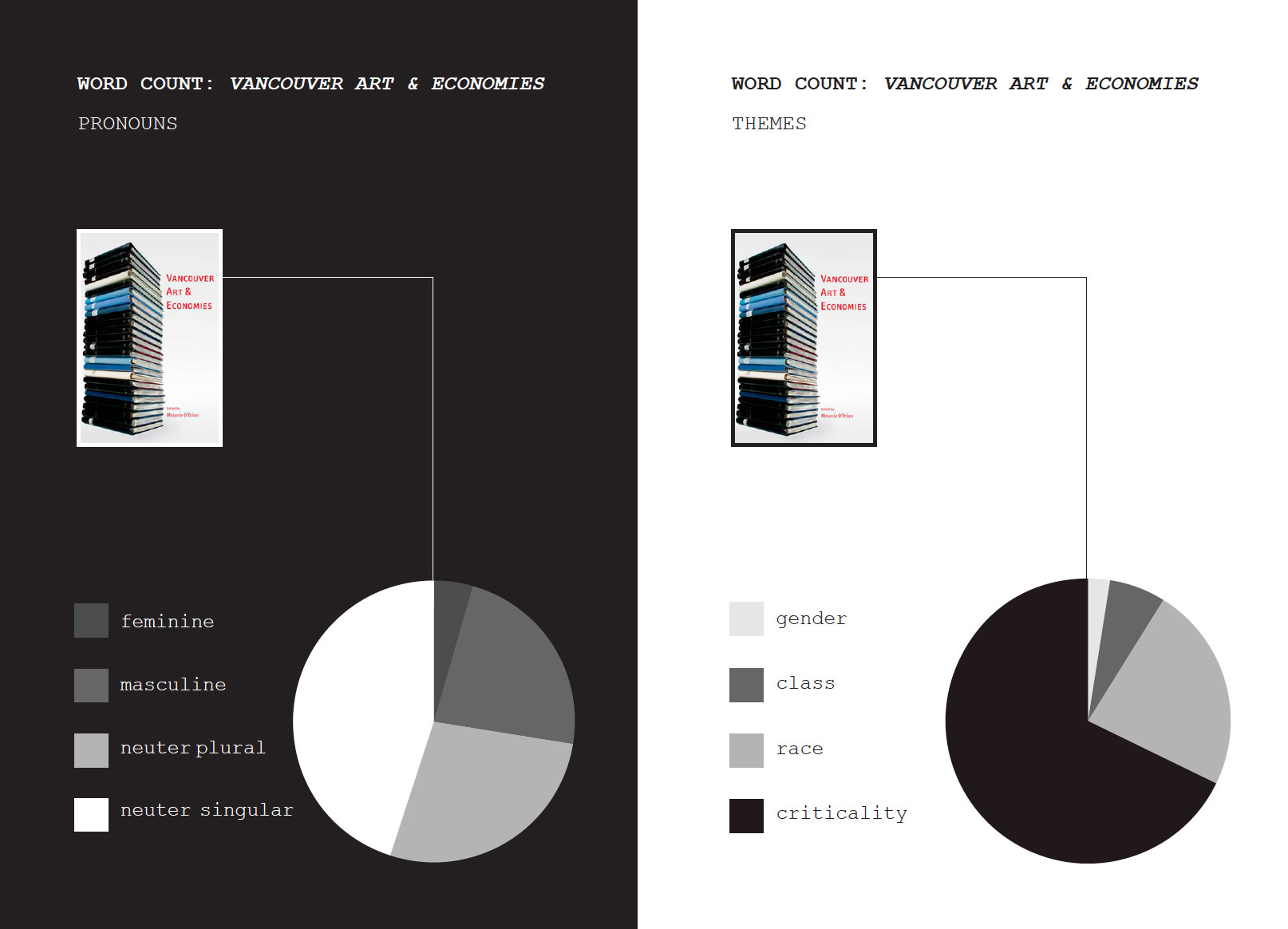

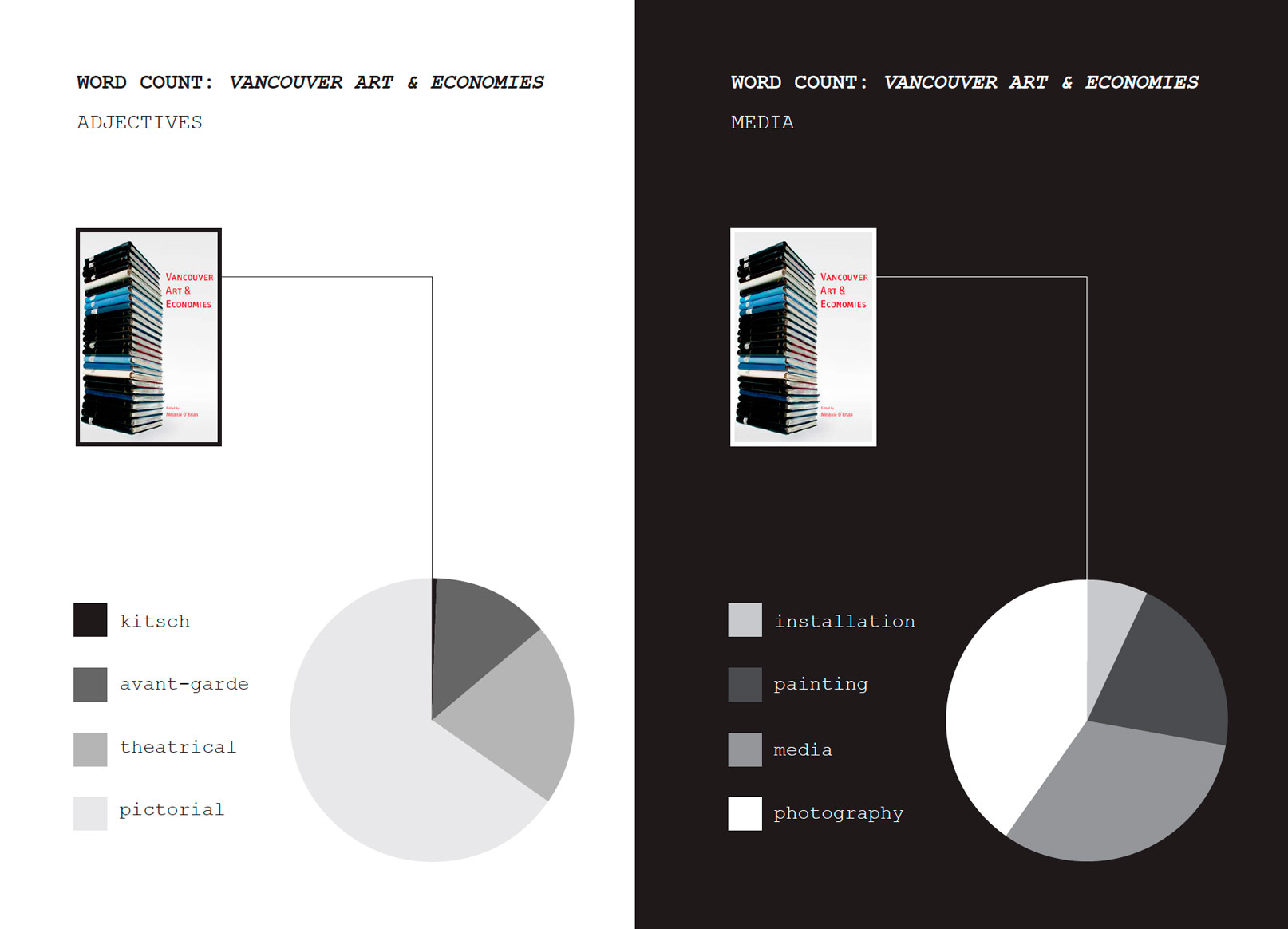

Apart from the very roughly sketched scenes I’m attempting to describe in my own efforts at reflection on the recent past, I won’t go further here to encapsulate the rich histories of the ‘60s into the new millenium, leaving that role to the many existing such texts and the excellent research, art historical essays and archival documents captured in publications such as Vancouver Anthology,11 Writing Class,12 Vancouver Art & Economies13 and the Vancouver Art in the Sixties14 website archive and hopefully to come in future texts as well. Instead I want to reflect on some thoughts that came out of the interviews and recordings gathered during my writing residency at Artspeak, with a focus on some of the responses, ideas and questions that have stood out and continue to resonate with what I see happening now; these are just a few of the lines that continually broke through the surface of the ongoing conversation that “never stops” —— for me they stand out in a way that warrants some reflection, interpretation and comment.

⁂

1. Vancouver Was Always an Anti-Greenberg Town

What I’m really wondering is where’s the rebel in Vancouver? In Edmonton, we had a huge modernist cloud hanging over us. The first generation went with it, but the following one rallied against it. Here, where’s the rally?

— Amy Fung

Vancouver was always an anti-Greenberg town. I recall when The Vancouver Art Gallery hired Terry Fenton, from Edmonton, as Director. But he said in the paper that Vancouver was way too into funk and that we need to see more Jules Olitski —— he actually said that in the paper. And the Vancouver artists wouldn’t stand for it. There was a big protest.

— Scott Watson

It’s not always easy to locate “the rebel,” a figure of shifting mythologies and imaginative conjurings at best. Vancouver artists resisted Greenbergian Modernism in a variety of ways, ranging from hippie lifestyle experiments to engagements with pre-Greenberg art history, challenging the notorious critic’s version of modernism with tactics ranging from an eager embrace of new media to working directly with language or by working with the body through performances or happenings. They shared in common the notion that a continued engagement with modernist abstraction was suspect and many considered it to be a sign of a conservative position —— for many it was just too “square” for the times, but also too representative of the still-dominant centre, New York, while standing in for domination and oppression in general. In spite of the concerns of some Marxist art historians (some of whom took their stand at the 1981 Modernism and Modernity conference in Vancouver to defend modernism from Clement Greenberg’s narrow version on the one hand and from postmodernist theories on the other),15 “postmodernism” (identified with a turn to text and photo-based imagery) was seen as the baseline requirement to work progressively for a growing number of artists by the ‘80s.

In Vancouver, influences from American and British Conceptual art, theories16 associated with the journal October and the art of the “Pictures Generation” combined with an abiding interest in art history and photography in the work of artists who later came to be identified as the dominant force for subsequent generations of artists to build on and to resist. According to the Vancouver Art Gallery, “Over the past two decades Vancouver has become internationally renowned for contemporary photo-based work, particularly the ‘Vancouver School’ of photoconceptualism that includes artists Roy Arden, Stan Douglas, Rodney Graham, Ken Lum, Jeff Wall, Ian Wallace and others.”17 As Julian Stallabrass has noted, Jeff Wall stands out as “one of the most prominent photographic artists on the contemporary art scene, and indeed one of the most successful artists working in any medium;”18 at the same time he is known to have made a point of aligning his photographic work with leftist theory through his early texts, while linking his practice to 19th century European painting, calling his pieces “pictures” instead of photographs. Textual supports played an important role in positioning Wall and his peers, with Wall himself once a prolific art writer, having been trained as an art historian as well as an artist.19 To be sure, writing art history is a way of ensuring entry into the archival mechanisms; by the mid-1980s Vancouver had established what artist Trevor Mahovsky has called a “community of text”20 where artists and critics would write textual supports for one another’s work, as catalogue essays and as critical reviews in publications such as Vanguard, Parchute and C Magazine.

But did all this pave the way for Greenberg’s ghost to make a recent return in Vancouver? Those tempted to frame this history in terms of psychoanalysis might call it the “return of the repressed;” however, the renewed interest in modernist abstraction is a tendency that ties into global trends more than it relates to any Vancouver-specific reaction. But at the same time it has had an air of rebellion (and sometimes apology) here it might not have otherwise enjoyed (and sometimes endured) —— here it is coming up against conceptual, new media and photo-based practices that have dominated Vancouver’s idea of “serious art” for more than thirty years. Where does such dominance come from? Undoubtedly it comes from multiple forces; perhaps it’s wrapped up in a desire to be contemporary and cosmopolitan that took artists towards photographic media. But another thing comes to mind that Bill Wood noted, “My idea about an oligarchy at the Western Front that I’d talked about in ‘This is Free Money?’21 may exist now among the local curatoriat,” an idea supported by Peter Culley’s comment that, “All power switched hands from the content producers to the curators.” It is something that raises more questions than answers with regards to influence, but it’s worth noting.

Scott Watson is a particularly influential curator in Vancouver; not only does he provide guidance for future curators in his advisory role in the Critical and Curatorial Studies Program at the University of British Columbia, he’s also responsible for career-making exhibitions through his role as Director/Curator of the university’s Helen and Morris Belkin Gallery. Recalling one particularly influential exhibition that contrasted sharply with the kind of work that had been associated with Vancouver, Watson offered visibility to art that had an air of rebellion in 1998 with an exhibition called 6: New Vancouver Modern. The exhibition featured work that, while semi-conceptual, features a low/high tension delivered with an irreverent attitude and deadpan humour. Although Watson emphasized the link to the “modern” for the work he included in the show, there was something of a continuation with earlier photoconceptual practices. The work in the show, while differing in tone from the “Vancouver School”, is mostly still tied to the photographic, the conceptual or the textual to some degree, though sometimes negatively and often comically; the biggest shift away from the “Vancouver School” was towards a less serious attitude while opening up to sculptural practices and drawing, thereby expanding the focus beyond photography.

A decade later, in the curatorial essay for another group exhibtion of up-and-coming Vancouver artists called “Exponential Future,” Watson acknowledges the career-launching power of such a show22 while continuing his argument for an engagement with modernism. As with 6, nearly all the work in the show, if not made up of photographs or video, at least references the photographic somehow, even if only as source material. The Exponential Future of the title is in contrast to the fact that such exhibitions function as powerful vehicles for a particular perspective on Vancouver art, thereby being somewhat selective about the future, nudging some aspects forward while leaving others behind. A couple of years later, a solo exhibition of Eli Bornowsky’s work curated by Jesse McKee stood out for an alternative engagement with modernism through painting and abstraction. It also stood out for taking place at an artist-run centre long associated with new media and performance. I remember wondering at the time if this was the only exhibition entirely composed of abstract painting to ever have been presented at the Western Front; it felt a little bit rebellious and even slightly scandalous in that context. By the mid-to-late-2000s, the non-representational could register as rebellious here. A renewed interest in abstraction and materials in both sculpture and painting made a return; at the same time irony and humour were turned down several notches. New arrivals on the scene who had already established themselves elsewhere, in other places where painting hadn’t felt quite so prohibited from being taken as “serious art,” included Elizabeth McIntosh who began teaching at Emily Carr in 2005, to name but one example. The shift became articulated at events such as the 2006 Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition PAINT, Robert Linsley’s talk delivered at UBC in 2010 that targeted once-dominant tropes and modes of working23 and the 2011 symposium Crossing Over: Painting A Critical Conversation at Emily Carr University. It’s hard to imagine these events happening a decade earlier. As Eli Bornowsky has said, “Now it’s not necessarily fruitful to say ‘the dominance of conceptual art’ or ‘photoconceptualism’. That’s not the case anymore.”

Writing through some of these episodes from the recent past is a way of stretching toward some kind of understanding. These recollections and quotes serve as vignettes that evoke a shift in feeling and tone in the art being shown and discussed in and around Vancouver; of course, these are my incomplete and biased recollections, as memories tend to be, nudged by the collected interviews and research to take shape here in this essay. On offer is a glimpse of a scene working through tensions around and between expanded ideas of modernism (and postmodernism), beyond the narrowly prescriptive version offered by Greenberg, but also beyond the confines of pictorial photography, between desires to keep Vancouver relevant in international art while negotiating its complex histories and its specific location in the world. As New York critics have started to register exhaustion with the enthusiastic return to the tropes of modernist abstraction,24 it will be interesting to see how Vancouver contends with the international flood of abstract art, but also how it will negotiate its photographically dominated recent past.

⁂

2. Once Upon a Time When Theory Was Cool

Artspeak was associated with theory and academia —— it was this new thing for a bunch of cool young people to start talking about continental philosophers, poetry and language.

— Keith Higgins

Towards the end of our interview, Judy Radul had said, “Just think about what’s so different that it’s hard to imagine today” —— one of those differences is the sense of excitement around “theory” in the mid-‘80s. More than just exciting, it was even cool to apply serious effort to try to decipher very difficult texts and to then enact that thinking somehow in one’s work as an artist. Looking back from the present time in 2015 when theory has become kind of uncool, and there has been a sense of exhaustion and frustration around theoretical art work for quite some time now, the excitement is difficult to imagine, not just for its vigour and intense intellectual focus, but for the context that supported it. Though there have been several recent reading groups, it’s difficult to imagine the intimate scale of a scene where excitement about texts could be shared and theoretical positions could be passionately argued; for generations coming after, it’s perhaps like it never existed.

But once it was cool. In answer to Amy Fung’s question of where’s the rebel in Vancouver, for a time the rebel artist was identified with an intellectual position. People felt they weren’t getting what they needed in the local universities and art schools, so they set about “re-educating themselves on their own time and their own dime,” as Bill Wood put it. According to Stan Douglas, “Between the talks, conversations and sharing books, it was in many ways a better education than the one I received in art school where there was not much respect for language.” Perhaps the greatest paradox of this “rebel” position was that Vancouver’s most notable art scene rebellion involved a “respect for language.” This went against wordless expression but also against counter-cultural, sensual hippie experiments with new media. It also went against existing art programs that were light on the intellectual engagement and theory; at the same time it went against the Social Credit party cuts to education.25 Finally, it went against contemporaries who had a sometimes aggressive, anti-intellectual punk attitude. But sometimes punk aggression met up with intellectual erudition, most directly (and mostly less aggressively) in music; as one example, the punk band UJ3RK5 included artists Rodney Graham, Jeff Wall and Ian Wallace and they had at least a couple of songs that dropped art historical references.26

Through regular discussions hosted by programs like Artists/Writers/Talks at Artspeak, people “developed the sort of knowledge of each other where you could really argue something and not cause a fistfight,” as Keith Higgins put it. Argumentation was key, and this new intellectualized channel for aggression seemed particular to the Vancouver art scene —— Cate Rimmer noted that people coming from out of town were surprised by being questioned so intensively about their work. Lorna Brown recalled that, “It was valuable conversation because it wasn’t altogether seamless,” and, “While it was convivial, there were critical challenges to visual artists using text.” An intellectual community had formed around conversation and debate, artists and writers. But over time, the ‘80s wave of intellectualization and art theory hardened, a risk possibly only glimpsed as a flickering one back when Ian Wallace performed At Work 1983 at the Or Gallery with the storefront window framing “a theatrical process of composing ideas and artworks” where “conventional artistic production is conflated with academic activity,” as Kathleen Ritter put it.27 About the scene that unfolded shortly after, Peter Culley went so far as to say, “Everybody was totally faking it with the theory in those days!” While there was a sincere interest on the part of some people who combined university education with participation in the art and literary scenes —— and as Peter Culley also noted, it invigorated some who were more comfortable with theory; for others it was a matter of keeping up and at least appearing to be intellectual in the way that carried the most weight at that time. At its most superficial it became about showing the signs of intellectual engagement with the right kinds of theory to enough of an extent to be included and to be successful with exhibitions and grant applications. Once theoretical engagement was no longer questioned as a requirement or in its content and form, it was perceived that “things have gotten way too polite” (as Culley put it). “Theory” became like a porcelain plaque for displays of intellectual erudition —— a precious object easily shattered instead of a living and vibrant mode of discussion. There was also unbending “fortress” theory that was repeated loudly, but soon the unspoken and the whispered weighed as heavily as the outspoken and the brazen.

In hindsight, of course engagement with theory wasn’t always the virtuous, progressive, social justice-oriented mode it was often assumed to be; sometimes theory was used as a bludgeon to deliver the knock-out blow to which there was no comeback. Sometimes it was used as obfuscation to cloud the subject under inpenetrable layers. Sometimes it was used as a means to elevate one group while excluding others. But engagement with various kinds of theory was also part of a genuine desire to figure things out and to move forward, or to engage with the potential of the “insurrection of subjugated knowledges.”28 As one artist put it, “I think for Vancouver it was about how to reinvent the art of commitment. There was a lot of discussion in terms of that you have commitment, but equally important was to find a new aesthetically compelling form to project that commitment. I think that was pretty important to Vancouver art. And the solution for finding that point of both commitment and something that was aesthetically interesting was through the supplement of theory, of philosophy, of poststructural texts, of texts about alterity, and so on.”29

⁂

3. Then There Grew An Entirely Bewildering Profusion of Texts

Everybody was totally faking it with the theory in those days! It was like this schoolyard thing: people were passing around books like Hal and The Anti-Aesthetic. — Peter Culley

There is little hope that any book on the aesthetic and the anti-aesthetic can have the coherence, not to mention the impact, of The Anti-Aesthetic, because practices and positions have multiplied so drastically. And even aside from the entirely bewildering profusion of texts, there is the fact that debate on these issues is intense but sporadic, so that it is not clear how to go about comparing positions.”30 — James Elkins

While at times the intellectual discoveries invigorated discourse around art, there was also a feeling that poststructuralist theories had a suffocating effect leaving no room to manoeuvre and no clear way forward. As Scott Watson said reflecting back on his essay for the exhibition catalogue for Behind the Sign, “The ‘critical’ atmosphere of deconstruction and the ‘death of the author’ …the theories around how we’re constructed subjects rather than agents within the system… My objection to that position —— one that most people considered a radical position in poetry and art —— is that it didn’t provide for the agency necessary to provoke social change.” A contradiction emerged from “the idea that this art had a virtue attached to it,” as Peter Culley put it, that it’s the right thing to do as an artist (and the only thing to do if you’re a serious one); the idea of virtue couldn’t persist in coming up against a perceived lack of agency of the subject that came with much of the theory popular in the art world at the time and thus at times “theory” itself was perceived as a corrosive force within art scenes here and elsewhere. When theoretical moves could be perceived as posturing, not only from outside the academic enclaves of the art world, but even at times within the universities, the credibility of such modes of working became questionable.

Another problem arose for the intellectualized-political mode when confronted with the contradictions inherent in the art that claimed this notion of “virtue:” art that claims to be the most critical and the most relevant artistic position at the exclusion of others, only proves to become the biggest betrayal when it is found to be as exclusive and as marketable as any other,31 that it simply slots into the system it was meant to deconstruct, activating those circuits rather than destroying them. As Andrea Fraser recently put it, speaking of artistic strategies that were influenced by the sociological theories of Pierre Bourdieu and came to be known as institution critique, “I’ve come to think that rather than being part of the solution, those strategies are often part of the problem,”32 noting that the disavowal required to embrace such strategies could be more damaging at times than beneficial.

An intellectualized position, while still valid particularly in academic environments, is also perceived by many artists today to be an outmoded, “no fun” and pointless stance leading to a dead end; it understandably holds little allure for generations coming after. The steep learning curve combined with the difficult and neverending work of grappling with “theory” requires great motivation, interest and belief in the outcome of the process. Belief in the sacrifices of time and energy as being somehow “worth it” or “necessary” would be required to pursue an engaged intellectual position as artist. Along with the strength to endure the inevitable contradictions, an artist requires the support of curators, dealers, granting agencies, peers and colleagues for work involving such intense intellectual endeavours. With “the bewildering profusion of texts” and requirements to appear —— on the scene, in exhibitions and in text —— an intellectual position impacts the ability to spend enough time for proficiency in the studio. If being an artist today comes down to choosing a path out of many, then some may understandably doubt the benefits of choosing a path that eclipses what was desired in the first place in setting out to be an artist. As other possibilities became apparent, many artists simply left the “bewildering profusion of texts” behind and found support for other ways of working. This opening allowed for other ideas of “engagement”, “commitment” and “criticality” to make a return; the risk is that such returns would be only ahistoric appropriations of a style and nostalgic regressions to older modes and practices. On the other hand, turning away from some kinds of theoretical work opens the way for other intellectual endeavours and it’s important to remember that studio work is intellectual to varying degrees and in a variety of ways. Any hard division there is a false one and any sort of intellectual engagement is inevitably going to be incomplete and partial, whether it’s combined with studio work or not. Working deeply with materials has been raised up in value while the promises and the requirements left behind from theoretical demands surrounding art have left lingering requirements “to know” and to articulate one’s work; at the same time there’s an impossibility of “knowing” that we experience as a strange paradox when faced with the glut of information at our fingertips, but it’s a feeling in step with larger epistemological crises.33

The “not knowing” feeling is accompanied by a sense of betrayal (a notion ascribed to waves of “progressive” art since there was such a thing as the “avant-garde”). It is the failure of younger generations to continue certain lines of work on the one hand and the failure of repeated artistic revolts, recently experienced as a turn away from “theory,” on the other hand. There was growing impatience with the apparent failure of the promise of “theory” to further the causes of social justice in any real and lasting way.34 In the ‘80s it became apparent that the problem was embedded right in language, and therefore right in the very institutions and the tools that artists and poets had hoped to use to counter oppression, a problem that spawned Language Poetry and informed the Kootenay School of Writing (KSW). But such movements are never entirely unified, and one response to this uneveness was the feminist splinter group of KSW formed in the ‘90s by Lisa Robertson, Christine Stewart and Catriona Strang —— Barscheit Nation seized the language of avant-garde aggressivity to generate forceful clouds of feeling and energy, choosing pleasure over stultifying seriousness while turning the masculine machine against itself. As Michael Barnholden said, “The fact that language intrinsically carries gendered messages has never seemed more explicit.”35 While the Barscheit Nation project made for powerful poetics, there remains the problem of how to develop the practice of writing that lies at the core of art history and art criticism, without losing the strengths of the more prosaic forms by collapsing them into literary fiction and poetic experimentation. There may be lessons to be gleaned from the “Giantesses” of Barscheit and from a writer like Nancy Shaw who was able to go between literary license and art historical research and writing.36

⁂

4. Never Multiple Enough

Towards the end of his life, Roland Barthes —— the theorist so elevated in ‘70s and ‘80s art scenes —— grappled with the impossibility of “the neutral.” He couldn’t deny the contradictions embedded in the text itself, ones he faced in the impossibility of an objective, neutral position from which to analyze and to write.37 He could turn some degree of power over to the reader, but he couldn't deny the power of the writer. The writer had to find a way to occupy a neutral position. But as Mark Lewis had said in his artist talk at Artspeak in 1986, paraphrasing Jacques Derrida, when it comes to “the neutral… you can be damn sure it’s the male, it’s the masculine.” He went on to say, “I don’t know if it’s possible to imagine a relationship without authority. Authority in some sense is part of any relationship, and it’s just how you’re going to, in some sense, complicate that authority.”38 If it’s impossible to escape a position of authority, then surely it’s worse to deny its existence than to own up to it; this problem is an ongoing issue for feminism, but one that could be extended and discussed as a central problem of the left, democracy and social justice in general. It’s often no surprise when corruption is exposed on the right; the right side of the political spectrum seems to come with some degree of paternalism, authoritarian attitudes and even a certain amount of corruption. It’s perceived to be far more scanadalous and a far greater betrayal when such failings are revealed on the left.39 Lorna Brown described the feelings of loss associated with lingering left-bank inspired artworld assumptions and expectations: “it’s the loss of an idealized notion of an artworld that didn’t exist anyway, a lost innocence. There is pain in realizing that everything is not equal, even in this field that likes to imagine itself as a meritocracy, or a place apart, operating under different rules.” In spite of the profusion of allowable positions and voices, institutions run on the violence of exclusion —— as Judy Radul said, “It’s very hard to create an institution or an entity that’s multiple enough… it’s Walter Benjamin’s theory, the idea that every act of civilization is also an act of barbarism.”40 At the same time, the need to document, present and exhibit —— to be included —— results in a situation where, “You wonder if the past won’t clog up the gears so much that the future won’t be able to come into being,” as Scott Watson put it. Meanwhile, artist Marina Roy noted that by “2006, I felt that Vancouver had already been institutionalized enough, that it was really hard to escape this grid of who’s legitimate and who’s not.” So, while there’s a profusion of texts, there’s also a repetition at work here that generates the intitutionalized grid of legitimacy, or it might be called “transmission” if it were to be framed in traditional art historical terms of artistic succession versus artistic invention.41

One zone of perceived neutrality, yet one beset with repeated attempts to critique its “neutrality” through what has come to be known as “institution critique”, has been the amazingly resilient professionalized and bureacratic backdrop for art. The professionalized scrim of art institutions ranging from artist-run centres to national museums and international art fairs persists as a semi-neutral curtain covering over the inner workings that generate legitimacy. While sometimes the trappings of “professionalism” are simply what’s required to get things done, some artists have been creative in avoiding or at least troubling some of the demands of professionalization, sometimes re-working the requirements to allow participation on other terms. However, it seems that most any terms are available to then be set within the larger “curtain” framing the stage of institutional presentation —— or if they are really successful, then the once-outsider terms become the new normative platform, the stage where things become recognized as “art,” but also where practices that advocate for social justice inevitably encounter the intractable problem of the “neutral.”

⁂

5. Mired in Bureaucracy, Committees, Paperwork, Applications

Sometimes we were on two or three boards at the same time. It had to do with the scale of the community at that time and the interest in setting up non-profit societies. There were a few people in town with experience in whipping together a constitution and a mandate and so forth. It seemed like one of those things that you just did.

— Lorna Brown

The term Artist Run Centre (ARC) is a complicated one. To me, it brings to mind bureaucracy, committees, paperwork, applications and a much older generation of Vancouver artists. From my understanding, there are a limited number of ARCs in Vancouver that are able to receive funding, and those spots have been filled”42

— Maya Beaudry

While the connections and communities fostered through non-profit societies are valuable, there arises a danger when the organization and structure for an activity take over to the point where they eclipse the reason for organizing in the first place. Some call it institutionalization, others call it bureaucracy. Intermedia was perhaps the first Vancouver artist-run organization to feel the intense pressures associated with public funding.43 When a desire to do something hardens into exhausting external demands while falling well short of desires, I wonder where that tipping point lies at which something that was invigorating becomes more of a burden than a boon. Keith Higgins mentioned a moment of realization for those running Kootenay School of Writing, who found they were putting in huge amounts of effort, “so that we can do something more interesting” only to find that “we’re not doing much of the ‘more interesting.’” There seems to be a point where the structure set up to do what’s desired winds up dictating the nature of what happens within it. In the case of KSW, part of the problem was in not being able to get the funding to properly sustain the school. On the other hand, for artist-run centres the problem could be identified as the onerous administrative demands that came with funding. Stan Douglas recalls, “When the Canada Council began demanding that artist-run centres draft five-year plans to get funding. There was a lot of hand-wringing with people asking themselves, ‘Should we accept this kind of funding? It will change who we are.’ They did, and it did.”

It’s a familiar story that different groups have handled in different ways and within different contexts, from Intermedia to Western Front, Or and Artspeak, but a shared result is that a given amount of energy is required for organizational concerns. Further, putting in time on the bureaucratic demands of the ARCs has been perceived as a requirement for up-and-coming artists, as a pre-requisite for inclusion and survival, seen as “paying your dues.” However, such demands are not applied or perceived evenly. As Marina Roy commented in our interview, “You see a lot of women in administrative roles, running art programs in the city, and it happens in the university, too; they don’t mind taking on the extra work;” and as Lisa Robertson has noted, “As women we are conditioned to serve others.”44 It’s also possible that those most at risk of exclusion feel a greater demand to “pay dues.” If this is the case, then it becomes another potential setback for women, apart from any of the usual kinds of discrimination, one where women are sidelined as their vital energies are poured into support tasks —— of course this does not apply exclusively and evenly to women. How Judy Radul articulated the institutional weight artists bear has stayed with me: “It seems necessary, but it also takes its toll. It takes its toll on the people who agreed to play those roles of managers and it takes its toll on the people who don’t feel like participating in that at all.” In an artworld based on participation, networks and sociality, how do these pressures play out today?45

These days it feels like the administrative and textual requirements have shifted and possibly intensified in some places and fallen away in other zones. Artists have had to find new entry-level venues to show their work. As Bill Wood noted, “A show at the Or or Artspeak is second level now; it’s no longer an entry-level showing out of art school.” New artists confronted with this situation, driven by desires to show their work and the need to make space to do so, host exhibitions in a casual way that allows them to participate in a scene and to gain exhibition experience, often through the convenient proximity of shared space that leads to a small community. These kinds of casual exhibition spaces seem to have gradually increased in Vancouver over the last decade or so, in spite of the notoriously escalating costs of space in the city. In contrast to the older ARCs, these loose-knit groups are often short-lived, dissolving as people move away, lose their space or simply move on. Where the older ARCs have some stability through established funding, possibly a building and a clearly-defined organizational structure and mission statement, the loose-knit temporary groups have more spontaneous motivations, fewer ties and less bureaucratic demands, but they tend to be fleeting. Added to the mix are commercial galleries ranging in size from small apartment galleries to large spaces such as Catriona Jeffries’ gallery and Equinox. What this change of terrain means for art in the city remains to be seen.

⁂

6. She Was a Knowledgeable Teacher

Yeah. Or like a glory hole or something and all of a sudden you have this space where interactions can happen that otherwise wouldn’t. Or your relationship with this person is based on your going through the similar threshold.46

— Matthew Post (Post Brothers)

He leaves it to others to give themselves to the whore called “Once upon a time” in the bordello of historicism. He remains master of his powers: man enough, to explode the continuum of history.47

— Walter Benjamin

It represented for me this untouched aura of male visual language, and this notion of universality that goes along with abstraction. I was interested in working with the impossibility of that kind of utopia because I feel so excluded.48

— Allyson Clay

Sometimes an exchange suddenly reveals an uncomfortable pillar of its power. Miguel Burr’s interview with progressive curator-artist Matthew Post (Post Brothers) is one such moment in that it contains an exchange that evokes how disavowed attitudes lie latent in our views and discourses in spite of our best intentions.49 The entire interview builds into something peculiar overall, but the height of its weird friction can be felt where a discussion of curatorial strategy turns to a recollection of a personal anecdote —— here the underlying forces of gender and sexuality suddenly become starkly visible. Post Brothers’ project The Hole Idea leads the interviewer to reminisce about his experience in South Korea of being in conversation with another man, gradually realizing over time that they had slept with the same woman; the fellow commented that it made them “hole brothers.” Realizing a need to counter any negative impression accompanying the anecdote, Burr says, “And just to offset my misogynistic tones to that statement about ‘hole brothers’, she was a teacher. She was a knowledgeable teacher.”

An exercise of reversing the gender roles in a dialogue such as the one described above reveals the complex nuances of sexual difference as these play out in language [see Appendix B]; the dialogue offers a glimpse of the shimmering power relations of such a social landscape. In the broader interview text, there’s a discussion of a promising curatorial strategy called ‘Asterism’ —— loosely based on Walter Benjamin’s notion of the constellation,50 it puts a set of unexpected reference points into play, seizing upon the “non-canonical” and creating “relationships” between them. Matthew Post described it as, “creating relationships between these things that are maybe not following rigid, already-expected structures.” Such curatorial strategies are often assumed to be critical and progressive, and yet the conversation leads into a list of names straight out of the postmodern literary canon, where it already begins to get surprisingly difficult to flip genders by coming up with female authors, even after decades of academic work towards an expansion and reworking of the canon.

As the dialogue progresses, the gender-reversal exercise becomes a comedy, with increasing frictions of terms that don’t quite match up, poor analogies and the overall failure of the exercise of re-gendering the text, culminating in the realization that once the genders are reversed, “he” doesn’t need the prop of respectability in the form of education and learning as an alibi for his promiscuity. While the gendered double-standard surrounding sexuality is well known, here it can be experienced as it breaks through the surface of a conversation where it has a special power in its allegorical relationship to art: in such an exercise, it becomes apparent that the conversation unfolds allowing certain subject positions while prohibiting others. It also becomes clear why simply reversing the roles or revising the canon doesn’t work very well: some are barred access to a certain threshold; or we might flip that around to see that it’s a way of being perceived (or not perceived) in relation to a certain threshold or the potential to break through a given limit. It’s about a form of solidarity that rests on exclusion: a brotherhood.

In considering art and text, if learning is sometimes used to shore up respectability, or to construct a grid of legitimacy, then what’s being excluded and why? Or, perhaps more importantly, why is such a prop required at all? What ‘threshold’ deficiency is being covered over? One clue can be gained from considering the position of the humanities now:

Today, there’s widespread concern that the humanities are losing ground —— as well as intellectual cachet, students and financing —— to the hard sciences on the one hand and business on the other.51Such real-world conundrums could be answered simplistically, by advocating a re-valuation of the sensual or a turn to “pure” experience or intuition in art and art writing, as compensation for an overly rationalized hubris at the core of favoured disciplines such as economics and science, (and once art history), but swinging so far the other way is a weak answer that avoids the difficult questions. On the other hand, attempting to make over the field of art into a more scientific discipline by turning to linguistics, psychology, ethnography, philosophy and cognitive science —— now with the potential of being aided by data mining technologies —— is an insufficient answer.

The scientific disciplines studying the human subject have a built-in limit: researchers can’t step outside the subject of study to gain the necessary scientific objectivity required to legitimate their work as science. Denying this limit is yet another dangerous ruse. And yet scientific discourse is so tempting as Nancy Shaw noted:

In this ritual as theatrical and dramatic romance, another set of rules remained latent in our play. What could be more thrilling than being saved from the brink of death by some scientific-God cum knight-errant — making a swift shift into the deadly world of patriarchal gender relations? (We should discuss this matter more soon.)52Aside from instances of intellectualization-as-prop and science-as-saviour, there are serious battles fought within the academy and in other institutions and organizations, knowing full well that the architecture is structured against some of us with stairs that transform into slippery ramps when approached by the wrong subject. Some of us imagine another place of learning, other tongues and other ways to carry out our work (or perhaps even to shirk work when best to be unproductive.)53 It becomes a matter of continually insisting on one’s complex subject position, fighting for the ways and means to allow it, while at the same time promoting the greater solidarity needed for survival; it’s a matter of being able to choose a direction from the myriad possibilities, maybe through forming a constellation of understanding at that moment.

Thinking involves not only the movement of thoughts but also their zero-hour [Stillstellung]. Where thinking suddenly halts in a constellation overflowing with tensions, there it yields a shock to the same, through which it crystallizes as a monad.54Returning to Walter Benjamin, so regularly referenced in the artworld, often revered and rarely questioned, we could wonder, “Should the notion of the ‘constellation’ be dismissed out of hand to avoid the peculiarly gendered tone to be found lurking within texts such as ‘On the Concept of History?’” Or perhaps Benjamin’s text could provide just one evocative example of how an ongoing and complex process of sifting and re-orientation is needed to decide what to bring forward and what to dismantle and leave behind; certainly Benjamin had important insights to offer, but it is equally important to sift such weighty texts critically to be selective about the attitudes carried within.

⁂

Why would they write?

There is no value placed in the writing itself, let alone the writer. A lot of great artists in this city are great writers. But they don’t write much. It’s a lot of work, but there’s no value attached to it here. Why would they write?

— Amy Fung

“Why write?” came to also be a question of how to write, or what we could say about art, not only in what’s said, but in how it’s said, without merely repeating the same old transmission lines. When it came to my writing residency at Artspeak, I decided to turn this question into a project of questions, an interview project that took up an investigation of art and text as its premise. As a starting point, I drafted a fairly conventional statement for an art history project:

One of Michael Fried’s main concerns about Minimal art in 1967 was that it “can be formulated in words.” Shortly after, Seth Siegelaub pointed to a condition that was already in play: we most often encounter art through textual representation as description or as idea. Conceptual practices turned to language as a primary form, thus rendering the object in the gallery secondary. In response to this pivotal point, Textuality is a research and writing project investigating the longstanding relationship between art and text with its roots in the textual turn of the late 1960s. Questions related to these conditions will be considered with a particular focus on Vancouver. What have been the repressed conditions of art’s relationship with text? How has text been incorporated into the field of art and to what effect? What is the core area of expertise for writing about art now? These questions and others will be explored through interviews, analysis of texts, and consideration of artists’ projects.Looking back, I fell short of what I set out to do; maybe it’s not something to be done with words alone. But also, the abstract itself reflects the dominant, New York-centric and over-simplified narrative of Conceptual art. As I worked on the research for this project, I began to realize something else important: in Vancouver, the relationship between visual art and language is distinct and marked by decades-long resistance to being marginalized as “provincial.” In one example of the ongoing negotiation of the question of how to go about being international, Scott Watson has articulated responses to Alvin Balkind’s 1966 “Beyond Regionalism” exhibition56 and has continued working with the tensions between regional and international in how he understands Vancouver art.

While my education in art history gave me some ideas about the international, I wanted to better understand what had happened in Vancouver. At one point, I summed it up in a question like this:

I’ve encountered tensions between image and text, art and theory, painting and photographic media, conceptual art and identity politics, throughout my research on this project. These tensions could be said to draw territorial lines through the Vancouver art scene of the last 40 years or so. How do these tensions come into play?

Of course my question is highly problematic in itself. Again and again, I’ve witnessed how Vancouver has been mythologized and how desire, feeling and various motivations are cloaked in reason. Pressures to analyze the field of art through study leads to a kind of hubris in approaching unaccountable things in a pseudo-scientific way with analytical lines thrown across a nebulous entity, now sliced and diced as the lines are drawn tighter. I found that I had to let go of my goal to some degree, to loosen the aim towards understanding and instead allow more of an acknowledgment of feeling, which ties right into academic trends embracing theories of “affect.”57 Accompanying a turn to affect, there have been recent experiments in art writing that approach the art object obliquely through fiction or poetics, using literary approaches instead of research and writing methods associated with the discipline of history —— clearly other methods are being sought as a strategies against the trap of false objectivity.

In art writing particularly, it is well known that often things stated as certainties are likely to be merely positions or possibilities on closer examination. Its authority is well troubled by now. After all the research and writing, “the entirely bewildering profusion of texts” remains unconquerable —— it cannot be mastered. But of course there are many ways to write about art, just as there are many ways to write about water; you could talk about its molecular structure or you could evoke what it’s like to stand in it up to your waist, to name just two of the many ways for contrast.55

Experimentation with art writing that ventures into literary writing is nothing new; even renowned art historian Rosalind Krauss has become more experimental in her recent writing.58 When established art historians like James Elkins and Alex Alberro acknowledge they no longer know how to go about the writing part of what they do,59 maybe I feel a little bit better and also a little bit worse about the prospects for art writing. But mostly a little bit better, a little less inadequate, a little less “behind,” and a little less like a fraud. Because perhaps the current conditions leave us all always feeling a little bit behind and somewhat fraudulent in the face of demands to be perpetually up to the second, heightened by the expectations around the constant flow and instantaneity of digital media —— changes that have made research so much easier, but focus so much more difficult.60

Finally, as is always the temptation in our expansive times, I took on way too much with this project. It is a project where I largely attempted to deal with the context for art in a certain time and place, but it became about everything and nothing; it became about that flow of conversation, about filtering, about keeping up and about never having enough time for adequate reflection because that’s not what our times want from us. I regret that while looking at plenty of art, and thinking about it, I didn’t get around to immersing myself in any work enough to write about it. Nor did I get to go as deeply as I would’ve liked into the problems that I’ve roughly sketched with this essay. I see this as potential for future work, mine or somebody else’s, along with a continued exploration of ways to go about art writing.

But why write? Through the course of my interviews and research, it came up several times: the problem of how undervalued writers are right now. I also heard stories from one writer of being shunned by members of the art community because of something written. Some write to pay dues, to help friends and colleagues, to position one’s own work, to build up professional status and to grow the CV. All those concerns aside, writing can become a form of understanding in some helpful ways, as long as it doesn’t become a rigid way of approaching what’s encountered and provided that “understanding” doesn’t harden into unmoveable fact where a rigid framework shapes all future analysis. If writing is taken to be always a situated endeavour, as “my truth at this moment” then it becomes a powerful way of sifting and deciding. Once the “entirely bewildering profusion of texts” has been recorded and transcribed, read, re-read, sifted, processed and analyzed according to one system, and then dismantled and reassembled according to another, you have to stop and say, “Well, this is what I think.”61 The resulting text won't be neutral —— it will carry with it ideological bias and contradiction, but the alternative is silence. We put it out there, and then, as Saelan Twerdy said, “We can hope that our writing can mean something in a way we can’t anticipate —— that it can bring a new audience into being.”62 We can’t entirely anticipate what our works and words will mean, but that’s the beauty of it. As Lisa Robertson wrote regarding language, “Neither coded control, nor indetermination prevail; they alternate;” “all text is divergence.”63 All text is divergence and with it countless possibilities are dispersed. From these, a choice64 is made of what to cultivate and what to leave in the dust.

///////////////////////// /////////////////////////////////// //////////////////////////// ////////////// /////////// ////////////////////////// ////////////////// ///////////// ////////////////////// /////////////////// /////////////////////////// /////////////////////// ///////////////////////// ////////////// /////////////// //////////// ///////////////// /////////////// /////////// //////////////////// /////////////////////// //////////////// ////////////////////////// ////////////////// ////////////// //////////////////// ///////////// //////////////////////// ///////////////////// //////////////// //////////// ////////////////// //////////// //////////////// //////////////////////////// ///////////// /////////// ////////////////// ////////// /////////// /////////////////// //////////////// ////////////////// ///////////////// /////////////// //////////// /////////////////// /////////////////// //////////////////// /////////////////// ///////////////// ////////// ////////////////// ////////////////// ////////////////// ////////////////// //////////////////////////// ////////////// /////////////////// ////////////////////// ////////////////// ////////////////// ////////////////// ////////////////// //////////////////////////// /////////////////// //////////////// ////////////////// ///////////////// /////////////// //////////// /////////////////// /////////////////// //////////////////// /////////////////// ///////////////// ////////// ////////////////// ////////////////// ////////////////// ////////////////// //////////////////////////// ////////////// /////////////////// ////////////////////// /////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////// /////////////// ////////////////////// /////////////// ///////////////////////// //////////////////// ////////////////////// /////////////////////////////////// ///////////////////////////// ///////////////////////// /////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////// /////////////// ////////////////////// /////////////// ///////////////////////// //////////////////// ////////////////////// /////////////////////////////////// ///////////////////////////// ///////////////////////// //////////////////// //////////////////////// ////////////////////////// ///////////////////// //////////////////// ///////////////////////////// ///////////////////// /////////////////////////////// ///////////// /////////////////////// ///////////////////////// //////////////// ///////////////// ///////////////////////////////////// ///////////////////// //////////////////////// ///////////////////////////// ///////////////// ///////////////////// ///////// //////////////////////// ////////////////////////// ///////////////////// //////////////////// ///////////////////////////// ///////////////////// /////////////////////////////// ///////////// /////////////////////// ///////////////////////// //////////////// ///////////////// ///////////////////////////////////// ///////////////////// //////////////////////// ///////////////////////////// ///////////////// ///////////////////// //////////////////// /////////////////// ////////// //////////// ///////////////// ///////////////////// /////////////////// ///////////// ///////////

Notes

1. Lisa Marshall, ed., Talk: A postscript to some recorded conversations about art and text, in and around Vancouver, (Vancouver: Artspeak, 2015). [❮]

2. Charlie Smith, “Cecil’s legendary stripper bar closes to make room for a new condo tower,” Georgia Straight, (Vancouver: Vancouver Free Press Publishing Corp., August 3, 2010), accessed June 3, 2015:

http://www.straight.com/news/cecils-legendary-stripper-bar-closes-make-room-new-condo-tower

Smith’s story involves an exchange between editor/writer Dan McLeod and two artists: “In 1967 over beers in the bar, Dan McLeod and artists Michael Morris and Glen Lewis devised the name Georgia Straight, hoping to attract free publicity” via all the weather forecasts announced on the radio for the Georgia Strait.

Also see Janet Mackie, “Goodbye to great Vancouver nights at the Cecil Hotel,” Georgia Straight, (Vancouver: Vancouver Free Press Publishing Corp., May 28, 2008), accessed June 3, 2015:

http://www.straight.com/blogra/goodbye-great-vancouver-nights-cecil-hotel

[❮]

3. As included in: Lisa Marshall, ed., Talk. Digitally transferred recording and transcription provided by Deanna Fong, PhD Candidate, English, Simon Fraser University; audio cassette tape labeled October 22, 1970 (Cecil Hotel) from the Roy Kiyooka fonds, Simon Fraser University. [❮]

4. Scott Watson, “Transmission Difficulties: Vancouver Painting in the 1960s,” originally published in Paint: A Psychedelic Primer (published in conjunction with the PAINT exhibition, Vancouver Art Gallery, curated by Neil Campbell, September 20, 2006 — February 25, 2007), ed. Monika Szewczyk, (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2006), pp. 14-27; via Vancouver Art in the Sixties website accessed on April 30, 2015: http://transmissiondifficulties.vancouverartinthesixties.com/pages/01 [❮]

5. Greenberg’s theories were already on the wane by the late 1960s as practices that became known as Conceptual art, Minimalism and Pop eclipsed Greenbergian Modernism to represent progressive art. Key texts in the discurive battles of the 1960s include:

Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” Art and Literature 4 (1965): 193-201. Rpt. in Art in Theory: 1900-2000, ed. Charles Harrison & Paul Wood (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 773-79.

Donald Judd, “Specific Objects,” Arts Yearbook 8 (1965): 74-82. Rpt. in Art in Theory: 1900-2000, ed. Charles Harrison & Paul Wood (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 827.

Robert Morris, “Notes on Sculpture 1-3,” Artforum 4:6 (1966): 42-4; 5:2 (1966): 20-3; 5:10 (1967). Rpt. in : Art in Theory 1900-2000, ed. Charles Harrison & Paul Wood (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 828-35.

Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” Artforum, Summer 1967. Rpt. in Art in Theory: 1900-2000, ed. Charles Harrison & Paul Wood (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 836-46.

[❮]

6. Watson, “Transmission Difficulties”

Also see, Nancy Shaw, “Expanded Consciousness and Company Types,” in Vancouver Anthology, ed. Stan Douglas (Vancouver: Talon Books/Or Gallery, 2011) 95.

Also see, the Intermedia page from Vancouver Art in the Sixties: http://intermedia.vancouverartinthesixties.com/

[❮]

7. Douglas Crimp. “Pictures,” October, Vol. 8 (Spring, 1979), 75-88. [❮]

8. Two particularly influential texts by Barthes:

Roland Barthes, “Myth Today,” Mythologies, tran., Annette Lavers (Jonathan Cape Ltd., London: 1972), translated from the French Mythologies (Editions de Seuil: Paris, 1957).

——— “Death of the Author,” Aspen (no. 5-6, 1967); also included in an anthology of Barthes’ essays, Image-Music-Text (1977). [❮]

9. Already in 1965, “the medium is the message” was a main theme of The Festival of the Contemporary Arts at the University of British Columbia (UBC).

See Watson, “Transmission Difficulties: Vancouver Painting in the 1960s”

Also see Keith Wallace, “A Particular History: Artist-Run Centres in Vancouver,” in Vancouver Anthology, ed. Stan Douglas (Vancouver: Talon Books/Or Gallery, 2011) 31. [❮]

10. Thierry de Duve once elucidated the dystopian distortion of democracy he saw evoked by Dan Graham’s 1977 piece Performer/Audience/Mirror; pacing in front of a full wall mirror, Graham describes the audience back to itself in real-time, or rather near real-time, never allowing enough time for reflection or for one’s own internal musings to enter into the flow of consciousness. DeDuve compares the effect to that of the non-stop flow of mass-media-saturated culture on politics.

Thierry de Duve, “Dan Graham and the Critique of Artistic Autonomy,” Dan Graham Works: 1965–2000, ed. Marianne Brouwer (Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2001), 51.

Also see Irit Rogroff: “…the art world became the site of extensive talking —— talking emerged as a practice, as a mode of gathering, as a way of getting access to some knowledge and to some questions, as networking and organizing and articulating some necessary questions. But did we put any value on what was actually being said? Or, did we privilege the coming-together of people in space and trust that formats and substances would emerge from these?

Increasingly, it seems to me that the “turn” we are talking about must result not only in new formats, but also in another way of recognizing when and why something important is being said.”

Irit Rogroff, “Turning,” e-flux journal, no. 0 (November 2008), accessed June 4, 2015:

http://www.e-flux.com/journal/turning/ [❮]

11. Vancouver Anthology, ed. Stan Douglas (Vancouver: Talon Books/Or Gallery, 2011) [❮]

12. Michael Barnholden and Andrew Klobucar, Writing Class: The Kootenay School of Writing Anthology, (New Star Books, 1999). [❮]

13. Melanie O’Brian, ed., Vancouver Art & Economies, (Vancouver: Artspeak, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2007) [❮]

14. Glenn Alteen, Lorna Brown and Scott Watson, ed., Vancouver Art in the Sixties: Ruins in Process: http://www.vancouverartinthesixties.com/ [❮]

15. Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, Serge Guilbault and David Solkin, 2004 ed., Modernism and Modernity: the Vancouver Conference Papers, papers presented at the Vancouver Conference on Modernism, March 12–14, 1981. (Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design).

The Modernism and Modernity conference held at the University of British Columbia in 1981 was a site of contestation where influential Marxist art historians such as TJ Clark and Thomas Crow argued for possibilities for continued engagement with “modernism” while challenging art critic Clement Greenberg and his by-then monolithic, narrow and proscriptive view of modern art. Greenberg’s views were by then tainted with charges of sexist, racist and imperialist tendencies and in spite of his early leftist-Trotskyite leanings, the writer had been largely discredited as a “conservative” critic by the ‘80s.

Reading the conference transcripts, it’s hard to miss the peculiarly gendered aspects that might be worthy of further investigation; Nicole Dubreuil-Blondin seems to have been selected to represent postmodernism, with challenges made to the crowd as well as to Greenberg. Given that the tone was distinctly polemical and even a bit aggressive, did these academics do more harm than good in their attempts to defend a well-rounded modernism? Or was it too little, too late, against too great of a tide in the sea change that was happening all over the Western world? With friends like these, who needs Greenberg?

[❮]

16. Saelan Twerdy has recently provided a useful summary of the various kinds of “theory” circulating in the art world over the last few decades.

Saelan Twerdy, “A Theory of Everything: on the State of Theory and Crtiticism (Part I)” and “A Theory of Everything: on the State of Theory and Crtiticism (Part II)”, Momus: A Return to Art Criticism, October 30, 2014, accessed online October 2014: http://momus.ca/a-theory-of-everything-on-the-state-of-theory-and-criticism/ [❮]

17. Vancouver Art Gallery website accessed April 27, 2015: https://www.vanartgallery.bc.ca/collection_and_research/permanent_collection.html [❮]

18. Wall’s pictorial photography somewhat follows the lead of his teacher, Ian Wallace, except that Wallace linked photography with the monochrome bridging photographic practices to mid-century modernist abstraction. Wall went back further referencing 19th century painting, most clearly in his early photographic works such as Picture for Women (1979, references Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère of 1882) and The Destroyed Room (1978, references Eugène Delacroix’s The Death of Sardanapalus of 1827, to name two examples. [❮]

19. See Julian Stallabrass for a critique of the discursive practices surrounding Jeff Wall’s work.

Julian Stallabrass, “Museum Photography and Museum Prose,” New Left Review (65, September–October 2010), accessed online:

http://newleftreview.org/II/65/julian-stallabrass-museum-photography-and-museum-prose

Also delivered as a lecture:

——— “The Artist As Critic / The Critic as Mouthpiece,” Julian Stallabrass, Bliss Carnochan Visitor at the Stanford Humanities Center, “on the peculiar case of Jeff Wall,” Stanford Arts Institute, video accessed in 2013: https://vimeo.com/11362161 [❮]

20. Trevor Mahovsky, “Placed Upon the Horizon, Casting Shadows”, Paper delivered at apexart, May 31, 2000. [❮]

21. William Wood. “This is Free Money: The Western Front as Facility, Institution and Image,” in Keith Wallace, ed., Whispered Art History: Twenty Years at the Western Front, (Vancouver: Western Front, Arsenal Pulp Press: 1993) 179. [❮]

22. Scott Watson, Exponential Future, exhibition catalogue (Vancouver: Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia, 2008). [❮]

23. Robert Linsley’s talk “A FAILED REGIONALISM” was billed as “a draft toward the conclusion of Linsley’s book length history of art in British Columbia,” delivered as a curatorial lecture at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Wednesday, March 10, 2010. [❮]

24. Jerry Saltz, “Zombies on the Walls: Why Does So Much New Abstraction Look the Same?” New York Magazine, June 16, 2014, accessed online at vulture.com, August 2014: http://www.vulture.com/2014/06/why-new-abstract-paintings-look-the-same.html [❮]

25. Michael Barnholden and Andrew Klobucar have provided a useful summary of the historical and political context in their Introduction to Writing Class: The Kootenay School of Writing Anthology. Michael Barnholden and Andrew Klobucar, Writing Class: The Kootenay School of Writing Anthology, (Vancouver: New Star Books, 1999). [❮]

26. The documentary movie Bloodied But Unbowed: Uncut provides some insights into the Vancouver punk scene of the ‘80s.

Susanne Tabata, Director, Bloodied But Unbowed: Uncut, (Canada: Tabata Productions, Knowledge Network, 2011).

[❮]

27. Kathleen Ritter, “Focus: Ian Wallace at Work”, Ian Wallace: At the Intersection of Painting and Photography, (Vancouver: Black Dog Publishing and the Vancouver Art Gallery, 2012), 279. [❮]

28. Michel Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended” Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976, trans. David Macey (Macmillan: 2003) 6–7, via Wikipedia entry on "post-structuralism" accesssed June 18, 2015: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-structuralism [❮]

29. This person did not want to be named, but is someone often identified with the Vancouver School. [❮]

30. James Elkins, “Introduction,” Beyond the Aesthetic and the Anti-Aesthetic, James Elkins and Harper Montgomery, ed., (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013). [❮]

31. Much Conceptual art came to be understood as anti-market and poltical in its refusal —— of the market, of aesthetics, and of expression, to name three of the most common claims —— but art historian Sophie Richard has found that Conceptual art, as it functioned in the art world, was much more market-oriented than previously assumed.

Sophie Richard, Unconcealed: The International Network of Conceptual Artists 1967-1977 —— Dealers, Exhibitions and Public Collections, (London: Ridinghouse, August 15, 2009)

[❮]

32. "There’s very little that we think of as critical art practice that does not in some way operate through strategies of appropriation, distanciation, reframing, displacement, or estrangement. In the past few years especially —— although this has been a development that’s been evolving for the past ten years for me —— I’ve come to think that rather than being part of the solution, those strategies are often part of the problem. That is, through those strategies, we in the art field often end up distancing what, in fact, are very immediate, material, lived investments in what we do."

Andrea Fraser, “Interview with Andrea Fraser, Part 1,” Bad at Sports: Women in Performance, October 8, 2012, website accessed May 25, 2015:

http://www.artpractical.com/column/interview_with_andrea_fraser_part_i/

[❮]

33. While I do not have a deep enough background in philosophy to properly address what’s been happening in terms of epistemology or in what’s been labeled as “speculative realism”, I've noticed a recent art world interest in philosophers such as Ray Brassier, Quentin Meillasoux and Reza Negarestani that suggests there are overlapping concerns here. [❮]

34. Other work and pressures are required for lasting social change, but likely with greater effect when performed in conjunction with intellectual and artistic activities. [❮]

35. Barnholden and Kloubocar, “Introduction,” Writing Class [❮]

36. There are literary writers who’ve gleaned from art (Kenneth Goldsmith, Michael Turner) and then there are art writers who’ve gleaned from literature (Maria Fusco, Lisa Robertson), plus art historians recently writing in more creative ways and less academically constrained ways (such as Rosalind Krauss, Carol Mavor and James Elkins). As a useful resource, see James Elkins for his research into the “writing” aspect of art history, collected in his blog “What is Interesting Writing in Art History”: http://305737.blogspot.ca/ [❮]

37. Roland Barthes had realized the impossibility of achieving “the neutral” late in life, as he continued to seek it, sharing the search with his students through lecture courses at the Collège de France, The Neutral

and How to Live Together in which “the critic spoke of his struggle to discover a different way of writing and a new approach to life. The Neutral preceded this work, containing Barthes’s challenge to the classic oppositions of Western thought and his effort to establish new pathways of meaning.” —— Columbia University Press

Roland Barthes, The Neutral: Lecture Course at the Collège de France (1977-1978), Rosalind Krauss and Denis Hollier, ed., trans., (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005)

—— —— How to Live Together: Novelistic Simulations of Some Everyday Spaces, Kate Briggs, Trans., (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012)

[❮]

38. As included in: Lisa Marshall, ed., Talk; transcription by Lisa Marshall; audio cassette tape labeled Mark Lewis, Burning, March 13, 1988, Artspeak archives. [❮]

39. By now “right” and “left” need to be rethought to develop terms more able to adequately discuss a complex global political landscape that’s hardly binary. [❮]

40. See full text for context: Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” Dennis Redmond, trans., 2005, Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike) Transcribed: by Andy Blunden; Original German: Gesammelten Schriften I:2. Suhrkamp Verlag. Frankfurt am Main, 1974; accessed online 2014: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/benjamin/1940/history.htm [❮]

41. As University of Oxford art history professor Gervase Rosser put it, “two problems (are) central to the history of art: the roots of artistic invention, and the transmission of styles and techniques.” Gervase Rosser, Gothic: Artistic Originality and the Transmission of Style in Medieval Art, University of Oxford, course description accessed May 26, 2015: http://www.hoa.ox.ac.uk/staff/courses/gothic-artistic-originality-and-the-transmission-of-style-in-medieval-art.html [❮]

42. Sunset Terrace (Maya Beaudry) and Scott Parsons, “Sunset Terrace: INTERVIEW BY SCOTT PARSONS”, The Editorial Magazine, 2014, accessed online 2014: http://the-editorialmagazine.com/?p=4767 [❮]

43. Keith Wallace, “A Particular History: Artist-Run Centres in Vancouver,” Vancouver Anthology, 31-3.

Also see Nancy Shaw, “Expanded Consciousness and Company Types: Collaboration Since Intermedia and the N.E. Thing Company,” Vancouver Anthology, 92-7.

[❮]

44. Brecken Hancock , “An Interview with Lisa Robertson,” Canadian Women in the Literary Arts (CWILA) website, accessed 2014: http://cwila.com/an-interview-with-lisa-robertson/ [❮]

45. Susan Cain has recently argued that extroversion has been a favoured trait in Western culture since the industrial revolution, connecting it with a cultural shift towards valuing personality over character. This shift has affected all aspects of Western culture, including the art world to some degree where sometimes sociality is mistaken for “socialist” and “social practice” is sometimes too readily associated with notions of “social justice.”

Susan Cain, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, (New York: Crown Publishing Group, 2012).

Both David Joselit and Lane Relyea have recently argued that the network has come to dominate the art world with the advent of globalization and the neoliberal economy. The term "network" can be taken in the technological sense of connected computing devices, but it can also be taken in the social sense of “networking” to collect as many contacts as possible, with the two main meanings of the word converging in social media applications.

David Joselit, After Art, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012)

Lane Relyea, Your Everyday Art World, (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2013)

The three examples above indicate that there may have been a shift over the past century that is two-fold, favouring outgoing salesmanship and networked structures —— a shift that is still unfolding today. This is an area in need of further research and analysis.

[❮]

46. Matthew Alexander Post and Miguel Burr, “New Conversations: Talking in Circles with Post Brothers”, 2012, Decoy Magazine. [❮]

47. Walter Benjamin, "On the Concept of History" [❮]

48. As included in: Lisa Marshall, ed., Talk; transcription by Lisa Marshall: audio cassette tape labeled Allyson Clay, June, 1988, Artspeak archives. [❮]

49. I don’t want to suggest that Burr and Post are setting out to be deliberately sexist, but rather that we are all subject to some extent to underlying social tendencies and pervasive attitudes that are just below the surface and are sometimes provocatively revealed through conversation. Such dialogue need not be censored, but considered for what it can tell us about the attitudes that shape our interactions and relationships in the world. The interview form as a kind of "entrapment" also crossed my mind here. [❮]

50. Walter Benjamin, "On the Concept of History" [❮]

51. Rachel Donadio, “Revisiting the Canon Wars,” The New York Times, (September 16, 2007), accessed online June 2015: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/16/books/review/Donadio-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1& [❮]

52. Nancy Shaw in Monika Gagnon, Nancy Shaw and Jody Berland, Let’s Play Doctor RX : Undoing the Ruse of Clinical Objectivity and Its Pathological Placement of the Feminine, (Vancouver, BC: Artspeak Gallery, 1993.) [❮]

53. I’m thinking of such projects as the Ladies Invitational Deadbeat Society and their turn around of such neoliberal expressions such as “Do more with less” into “DO MORE WITH MORE/DO LESS WITH LESS”, and also of Lisa Robertson’s quotation of Hannah Arendt on lathe biosas: “Arendt cites the ‘lathe biosas,’ live in hiding, one of the tenets of the Epicurean School of Athens. An alternate translation of Epicurus’s term is ‘live unknown;’ in either case, for the Epicurean, the thoughtful retreat from the exigencies of a public life is to be preferred to an immersion in the propagandistic deisms and extremist propulsions of the market, mass representation, warfare and state-sanctioned religion.”